|

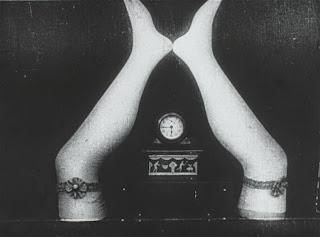

| Stills from "Pretty Hurts." |

In an interview with Tavi Gevinson, Lorde remarked of BEYONCE: The Visual Album (2013), "I would cry if I had to make that much visual content for an album!"

Yup, that's the point. BEYONCE: The Visual Album is a massive spectacle of occluded labor, an album that was released as a surprise, for which the question "How did she do all that?" was superseded only by "and how did she keep it a secret?" This is the narrative of perfection: all this work, made to look easy.

It seems telling that these are the refrains with which female labor, especially that of the "working mom," is greeted. Here are my top results for a Google Image search on "working mom":

|

| Top Google Image search results for "working mom." |

How does she do it? She makes it look effortless, and all the more so because we know it isn't. Repeatedly, Beyoncé trains the camera on her own beauty and the making of that beauty, and the effect is not to demystify (as in the infamous Dove ad of nearly a decade ago) so much as to centralize Beyoncé's accomplishment. The always-loaded-in-advance can women have it all? undertone to the question of can Beyoncé do it all? offers much of the album's driving tension. Clearly, as the album's success attests, Beyoncé can do it all, and yet the relentlessness of the question taps into a current of pain that seems to be female success's necessary concomitant.

|

| "Yoncé": "Tell me how I'm looking, babe." |

[I guess now is the time to observe that if you want a truly educated take on this album, it is this excellent review by Emily Lordi.]

In "Pretty Hurts," the album's first track, instead of the passive model in the Dove video whose image is altered by countless unseen agents' hands, we see a young woman deploying all the more or less painful tricks of the trade—curlers, ripping out upper lip hairs, Vaseline on the teeth (what), and, inexplicably, apparently Lysoling herself in the face (this part I truly don't understand—is it hairspray? Glade??). Although she's sometimes aided by others (at one point a woman in what looks like a HazMat suit spray-tans (?) her), mostly she has learned these techniques herself and applies them to her own body.

The video continuously cuts between before, during, and after the fictive pageant: the hours of self-crafting, the show itself, during which a losing Beyoncé has to smile and clap convincingly as another woman is crowned, the bitter aftermath. The cuts show that this is not a simple sequence of before, during, and after; preparation is always ongoing, evaluation is always ongoing, self-loathing is always ongoing. This is nowhere clearer than in the "backstage," supposedly nonperforming scenes in which Beyoncé's face snaps in and out of obligatory smiles:

|

| I want to point out that these screen shots were very hard to capture, because the transitions in and out of smiling happen so quickly. |

In fact, at one point she pulls on a smile as a man is in the process of yelling at her:

Pretty "hurts," but more than that, it's work, all kinds of work, and years of it, as we learn from the video's grainy final footage of an infantine Beyoncé Knowles, her name mispronounced by the announcer, winning a contest. "I love you, Houston," says the well-trained child, who has done what was asked of her and won.

"Pretty Hurts" announces what emerges as the whole album's preoccupation: Bildung, the making of Beyoncé and BEYONCE, the labor of performance, and not just performance as a single punctual event, but rather as a process of self-making that begins in childhood and warps time. "I do it like it's my profession," she murmurs in "Rocket," in one of the album's many unnerving invocations of sex work—unnerving because, even though she is talking about sex, it's something that could be said of almost anything Beyoncé does. What could be more professional than shooting seventeen music videos in secret while also on tour? When the song tacks on, "By the way, if you need a personal trainer or a therapist, I can be a piece of sunshine, inner peace, entertainer...," it's gratuitous; we already know—got it, Beyoncé, you can do it all! But the listing of professions in the midst of this supposedly romantic sex ballad, visualized mainly through shots of Beyoncé in lingerie, also calls attention to the professionalism that runs through everything. She can be a singer and a sexual fantasy—also a personal trainer, a therapist, a certified public accountant, a skip tracer, whatever. It's just one more thing when intimacy itself is a job.

The invocation of sex work also appears in "Partition," which opens with the infamous napkin-drop:

|

| [source] |

There's a way that this video is all over the place, and another way in which it isn't. The video frames the song's lyrics as the fantasy of a neglected wife, so unseen by her husband—whose point of view the camera eye offers us—that his newspaper covers up her face at the breakfast table.

But while we are ostensibly in the neglectful husband's visual position, we are disallowed from adopting it: the newspaper is blurry, whereas the edge of Beyoncé's hair is in focus. The video proposes a contrast between Neglected Beyoncé and Sex-in-a-Limo Beyoncé as if these were mutually exclusive roles, but only to undermine that contrast. "Partition," even more than "Rocket," insists on the labor of being a Hot Wife. Mia McKenzie reads the Napkin Drop playfully:

One of my favorite scenes in all of Beyonce’s new videos is in “Partition” when she drops that napkin just so that white woman has to pick it up. I read it as an incredible moment wherein a powerful black woman flips the script on white women who are constantly trying to put her in “her place” and in one subtle movement puts them in theirs.This reading is appealing on its face, but I think it also gets at one of the many tensions through which "Partition" operates: the ostentatious dropping of the napkin performs Beyoncé's status as mistress, not servant, but only "flips the script" because the racial politics are obvious, because we know how typically the reverse dynamic holds. We can enjoy the flipped script, but not without knowing that it's flipped, not without marking the threat that the black woman will always somehow be pulled into a role of servitude. It's the same threat that emerges in Jay-Z's infamous quotation in "Drunk in Love"—"Eat the cake, Anna Mae," a citation and apparent embrace of Ike Turner's violence against Tina Turner. Wait, more violence against black women? Again? Are we supposed to be okay with this? But it's the script (literally—from What's Love Got to Do With It) that most of "Drunk in Love" is flipping. Don't get too giddy about flipped scripts, Beyoncé seems to say. They can flip back.

A brief detour on black women flipping things around.

Consider the "topsy-turvy doll," a popular nineteenth-century toy depicting a white doll who, when her skirt was flipped over her head, revealed a black doll on the other side, and vice-versa, supposedly first made by enslaved women for the white children for whom they cared.

|

| Robin Bernstein discusses these dolls in Racial Innocence, especially pp. 81-91. |

As Robin Bernstein puts it in in Racial Innocence,

A child who minimally followed the implied script by incorporating the skirt-flip into play felt the balance of the doll, the fact that the poles weighed equally in the hands as the doll rotated. The thing scripted its user to position neither black nor white permanently on top; the competent user received the thing's message that the hierarchy could—and should—flip. With this thing, enslaved African American women scripted racial flip-flops, a perfomance of black and white in endless oscillation rather than permanent ranks of dominant and oppressed. (88)

The history of literal racial flipping scripted into African American women's artistic production looks different from the vantage point of 2013's "Queen Bey." As cleverly subversive as it is for an enslaved black woman to give her five-year-old white mistress a doll that performs hierarchy-reversal before her eyes, its proposed legacy in a rich black woman's deliberate napkin-drop has more ambiguous resonances. Script-flipping can feel wearisome—oh, that's still the script? The topsy-turvy inconsistencies of the album's positions, which have launched endless "Is Beyoncé feminist?" wars, mark the instability of hierarchy even for a black woman who has ostensibly made it.*

This instability is all the more precarious for its location at the sites of intimacy and sex; as the topsy-turvy doll also demonstrates, the flipping of scripts often occurs in the flipping of skirts, through the sexual violence with which black women are historically disproportionately targeted. "[T]he African American dollmaker sent that [white] child to bed with a sign of systematic rapes committed by members of that child's race, if not that child's immediate family," Bernstein notes. "She tucked beneath the child's blankets...a sign of the child's enslaved half-sibling, either literal or symbolic." (89) The multiple ironies of the skirt-flipping topsy-turvy doll prefigure the difficulty of pinning down a political read on a spectacle of occluded labor, a black woman whose success is so bound up in the spectacularization of her nearly-nude body.

|

| Josephine Baker |

Servitude is always at issue in "Partition," which is why the song's primary addressee is not the lover (as in "Rocket") but the limo's "driver." Seconds after establishing her difference from a servant with the napkin-drop, she sings, "Driver, roll up the partition, please;/ I don't need you seeing Yoncé on her knees." The partition, with its ability to be rolled up or down, signifies the instability of this character's place in the household. Maintaining her position as "mistress" involves not being seen "on her knees" by the servants. For whom is she performing?

Rolling up the barrier between driver and speaker, in other words, again marks the class difference between them but also the threat of that difference's flimsiness. The element of performance and of professionalism recurs with each repetition of the song's refrain: "Forty-five minutes to get all dressed up,/ And we ain't even gonna make it to this club." Getting dressed up was work, we keep being reminded. Forty-five minutes of work, 0.75 hours. This is the complaint of someone mindful of the clock.

This is why the B theme, addressed to the lover, makes so much sense. Beyoncé sings "Take all of me; I just wanna be the girl you like, the kind of girl you like" across shots of her almost hilariously spectacularized body, first just writhing in some sort of beaded wig, but quickly multiplied as what Siegfried Kracauer called the "mass ornament." Multiplied in avant-gardist seriality, the spectacle of Beyoncé's body is rendered generic and, at the same time, sublime in its sheer repeatability.

Oh, whoops, that's from Fernand Léger's Ballet mécanique (1924). Here's Beyoncé and some extra appendages:

The boundary between "the girl you like" and "the kind of girl you like" is as permeable as a limo partition (with the "chauffeur

It's not a big hop from there to Beyoncé in a cage with leopard spots, Jay-Z creepily looking on while smoking a cigar, in a move that Charing Ball quite reasonably called "groan-inducing."

Groan-inducing because it's the script, not the flip. The partition is down. And as with Josephine Baker, we can't decide if she's exploited, self-exploiting, or winning.

"I do it like it's my profession" indeed: there's a fine line between being professional and being a servant, especially if your fame and fortune rest on the commodification of your beauty and (feminine hetero-)sexuality. Sex is performance; being sexy is performance. The "Partition" video precisely cashes in on what it also critiques.

* * * * *

Part II, if/when I get around to it, will deal with Baker's and Beyoncé's glittering surfaces and the glinting conundrum that is "***Flawless."

* * * * *

*I think it's fair to say that the album does not meaningfully explore any alternative to hierarchy, which is why oscillatory scripting and script-flipping seems to mark the richest sites of its political imagination.

Thanks to @SpringaldJack for the "Partition" lyrics correction.

Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood and Race from Slavery to Civil Rights. America and the Long 19th Century. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

Cheng, Anne Anlin. Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Kracauer, Siegfried. The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995.

I'm really interested in hearing your thoughts on ***Flawless after reading this!

ReplyDelete