Monday, August 25, 2014

Well, it's been a good seven years on this janky Blogger blog, but I've finally decided to move to a minimally less janky site. Here it is.

Thursday, August 21, 2014

[Y'all, I was going to write about "***Flawless," but then Beyoncé released a remix ft Nicki Minaj and you guys I'm just going to need a little more time.]

Thursday, August 14, 2014

International Modernisms 1840-present: Shock, Electricity, Invention

MA seminar, autumn 2014

In 2010, the Museum of Modern Art in New York ran an exhibition titled Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925. Illustrated by a large, international network diagram covering an entire wall at the exhibit entrance, the show thematized invention, with its technoscientific resonances, as much as abstraction. The idea that the European and North American artists featured in the 2010 show had “invented” abstraction as an artistic principle would come as a particular surprise, however, to visitors familiar with an earlier, enormously influential MoMA show, “Primitivism” in Twentieth-Century Art (1984), which framed modernist abstraction in conversation with African and Oceanic art. This seminar will closely interrogate “invention” as an aesthetic desideratum across the long modernist moment, examining how its association with technological modernity relies in part on the production of a “tradition”-oriented “primitive” whose modernity is permanently deferred, yet whose art can be appropriated for modernism as a means of invigorating a declining civilization. This graduate seminar will investigate the workings of aesthetic modernism in relation to the modern ideologies of time, progress, and development on which “invention” relies, paying special attention to psychoanalysis and anthropology.

MA seminar, autumn 2014

In 2010, the Museum of Modern Art in New York ran an exhibition titled Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925. Illustrated by a large, international network diagram covering an entire wall at the exhibit entrance, the show thematized invention, with its technoscientific resonances, as much as abstraction. The idea that the European and North American artists featured in the 2010 show had “invented” abstraction as an artistic principle would come as a particular surprise, however, to visitors familiar with an earlier, enormously influential MoMA show, “Primitivism” in Twentieth-Century Art (1984), which framed modernist abstraction in conversation with African and Oceanic art. This seminar will closely interrogate “invention” as an aesthetic desideratum across the long modernist moment, examining how its association with technological modernity relies in part on the production of a “tradition”-oriented “primitive” whose modernity is permanently deferred, yet whose art can be appropriated for modernism as a means of invigorating a declining civilization. This graduate seminar will investigate the workings of aesthetic modernism in relation to the modern ideologies of time, progress, and development on which “invention” relies, paying special attention to psychoanalysis and anthropology.

Monday, July 7, 2014

On the "neoliberal rhetoric of harm"

I was disappointed to read Jack Halberstam's recent essay on trigger warnings and the "neoliberal rhetoric of harm." I agree with Robin James's assessment— that there's a real problem that JH is putting her^ his finger on, namely the potential for the language of trigger warnings (or, as second-wave feminists would have seen it, the language of "offense," as opposed to "oppression") to psychologize and individualize harm and render it unavailable to structural analysis. Moreover, such psychologization risks flattening all harm into the subjective experience of harm, making it difficult to distinguish between more and less crucial targets of critique. So far so good, and not so different from what many feminists already believe.

Where it goes off the rails is the suggestion that people engaged in social justice work need to, so to speak, "man up":

In short, an ostensibly feminist blog post about how feminists are humorless and need to lighten up is a little hard to take. No, having a pet parrot join the choir invisible is not as bad as lynching, but is that really what people are saying when they say they are sad about their parrot? Can we not have compassion for small griefs?

I have two basic observations to make about this, one about feminist critiques of neoliberalism and one about generations.

1. Neoliberalism and feminism

As Keguro Macharia pointed out, Halberstam's polemic can easily be read as a call for resilience, the neoliberal virtue par excellence. Indeed, Halberstam literally "call[s] for accountability," that language of counting and accounting that, as John Pat Leary has so brilliantly explained, takes as its baseline the belief that everything that matters is accountable. Halberstam's polemic, with its belittlement of college students as "naked, shivering, quaking little selves," is plagued by a bigger problem: how to mount a feminist critique of neoliberalism when neoliberalism operates through hypertrophied forms of femininity?

As misguided as Tiqqun's Theory of the Young-Girl is, it is symptomatic of the gendered realization of neoliberalism: what Karen Gregory calls "hyperemployment," and what Robin James, following Michelle Murphy, calls the "financialized girl." Such critiques, as well as formulations like Jodi Dean's "communicative capitalism" and Corsani and Lazzarato's "feminization of labor," demonstrate that, often, neoliberal exploitation succeeds by ramping up and extending the ways that women have typically been exploited under earlier forms of capitalism: in care work, emotional labor, unpaid labor, collaborations ("teamwork"), etc. (I'm mentioning just a few sources, but there's an enormous literature on this.) Importantly, innovations that began as accommodations for working women—"flex time," telecommuting, teamwork— became normalized or hypertrophied (as e.g. freelancing) as ways of reducing overhead and making employees interchangeable (disposable), to the point that a paean to nonstop work like Lean In could be marketed as feminism.

The forms that Halberstam critiques—safe spaces and trigger warnings, specifically, but also psychologization and subjectivity—really are forms through which neoliberalism can operate; indeed, maybe they are primarily modes of individuating harm and defusing structural critique. But they are also deeply feminized, as Gayatri Spivak pointed out in a famous reading of Freud's line, "a child is being beaten," and have the double-edged power of interiorizing (rendering unavailable to structural critique) and acknowledging women's psychology as complex. When neoliberalism takes feminized forms, it is difficult to attack neoliberal forms (here, subjectivization, safe spaces) without being flatly sexist. And the form that Halberstam's critique takes seems to me to succumb to that difficulty.

2. Generational relationships to history

There's another strain to Halberstam's polemic that pits professors against students on generational terms. Here is one generation who fought hard for queer rights; who never had a Gay/Straight Alliance in high school or a way to grow up both queer and normal. Who made careers out of queer studies while they watched their administrations professionalize and their faculties casualize, who teach at universities that cost $44,000 a year to attend.

A representative of this generation calls another a bunch of babies. (So they are: their infantilization has been enforced by the privatization of public goods, by debt, and by the destruction of good jobs. Reaching puberty earlier and earlier, likely due to environmental factors, they achieve financial independence later and later, if ever. All their own fault, no doubt.)

Halberstam kind of makes a big deal of this generational gap, pointing to the "friendly adults" who erroneously install "narratives of damage that they [the youth] themselves may or may not have actually experienced." It's as if young people are stealing an earlier generation's trauma, claiming it as their own when really they have it so good. In this bizarrely counterfactual linear temporality, the past is not only past but also dead, and you do not have the right to be traumatized by historical memory, only by things that have literally happened to you—even if you are eighteen and it's all—all—news to you. We (the older generation) were there, and are over it, and so you (the younger generation) should root yourselves entirely in the ameliorated present* and get over it, because it is over.

The result is an odd polemic against coddled millenials and their too-sensitive feelings, as if it were somehow ridiculous to be young and too sensitive, or for that matter, old and too sensitive. This cross-generational call to "get over it" is an example of what Sara Ahmed has called "overing": "In assuming that we are over certain kinds of critique, they create the impression that we are over what is being critiqued." It's particularly perverse to demand that young people be "over it," when they have perhaps only just left their parents' homes, and have perhaps only recently come to any political consciousness at all. There's a very good reason college students aren't "over it"; they just got there. Have you met a college student? It's all, all new.

It is its own kind of shock to learn about how you have been historically, rather than personally, hated. It is not about "trauma" but about developing a political consciousness that is also historical, a fundamentally utopian impulse to exist in solidarity with the dead. There is, to be sure, a fine line between identifying with the past and appropriating it, but I think we can allow our students some leeway in figuring out where this line is, and not getting it right every time. Certainly grown-ups need the same leeway.

And finally, it is particularly odd to issue a generational call to turn to environmental concerns instead of LGBT activism:

In the words of a famous owl: O RLY?

"Don't worry about safe spaces because we 'friendly adults' already fixed that for you (whether you feel it or not); do worry about climate change because we really fucked that one up."

Well, yes we did, but maybe it's therefore our job to do the heavy lifting on that one.

I think reasonable people can disagree about trigger warning policies per se. But I don't know how any adult dares be intellectually ungenerous with the young, considering the world we've collectively brought them into. My students can take a joke, and make one. They're hilarious. And they also care about one another and try not to make those jokes at one another's expense. They're not "over" anything because they're just getting started. I'm glad they are.

-----

^Although I was not aware of a preferred pronoun and had been given to understand that Jack Halberstam does not explicitly prefer pronouns of either gender (source), two commenters have suggested that masculine pronouns are preferred. Thanks to these commenters for the correction.

*I'm granting for the sake of argument that the oppression of queer (whether "really gay" or not) youth is really the non-problem that Halberstam claims it is, but in reality this claim seems to me to be premature.

Thanks to Robin James for a helpful discussion of this piece.

Your regularly scheduled Beyoncé posts will return soon.

Where it goes off the rails is the suggestion that people engaged in social justice work need to, so to speak, "man up":

In a post-affirmative action society, where even recent histories of political violence like slavery and lynching are cast as a distant and irrelevant past, all claims to hardship have been cast as equal; and some students, accustomed to trotting out stories of painful events in their childhoods (dead pets/parrots, a bad injury in sports) in college applications and other such venues, have come to think of themselves as communities of naked, shivering, quaking little selves – too vulnerable to take a joke, too damaged to make one.

In short, an ostensibly feminist blog post about how feminists are humorless and need to lighten up is a little hard to take. No, having a pet parrot join the choir invisible is not as bad as lynching, but is that really what people are saying when they say they are sad about their parrot? Can we not have compassion for small griefs?

I have two basic observations to make about this, one about feminist critiques of neoliberalism and one about generations.

1. Neoliberalism and feminism

As Keguro Macharia pointed out, Halberstam's polemic can easily be read as a call for resilience, the neoliberal virtue par excellence. Indeed, Halberstam literally "call[s] for accountability," that language of counting and accounting that, as John Pat Leary has so brilliantly explained, takes as its baseline the belief that everything that matters is accountable. Halberstam's polemic, with its belittlement of college students as "naked, shivering, quaking little selves," is plagued by a bigger problem: how to mount a feminist critique of neoliberalism when neoliberalism operates through hypertrophied forms of femininity?

As misguided as Tiqqun's Theory of the Young-Girl is, it is symptomatic of the gendered realization of neoliberalism: what Karen Gregory calls "hyperemployment," and what Robin James, following Michelle Murphy, calls the "financialized girl." Such critiques, as well as formulations like Jodi Dean's "communicative capitalism" and Corsani and Lazzarato's "feminization of labor," demonstrate that, often, neoliberal exploitation succeeds by ramping up and extending the ways that women have typically been exploited under earlier forms of capitalism: in care work, emotional labor, unpaid labor, collaborations ("teamwork"), etc. (I'm mentioning just a few sources, but there's an enormous literature on this.) Importantly, innovations that began as accommodations for working women—"flex time," telecommuting, teamwork— became normalized or hypertrophied (as e.g. freelancing) as ways of reducing overhead and making employees interchangeable (disposable), to the point that a paean to nonstop work like Lean In could be marketed as feminism.

The forms that Halberstam critiques—safe spaces and trigger warnings, specifically, but also psychologization and subjectivity—really are forms through which neoliberalism can operate; indeed, maybe they are primarily modes of individuating harm and defusing structural critique. But they are also deeply feminized, as Gayatri Spivak pointed out in a famous reading of Freud's line, "a child is being beaten," and have the double-edged power of interiorizing (rendering unavailable to structural critique) and acknowledging women's psychology as complex. When neoliberalism takes feminized forms, it is difficult to attack neoliberal forms (here, subjectivization, safe spaces) without being flatly sexist. And the form that Halberstam's critique takes seems to me to succumb to that difficulty.

2. Generational relationships to history

There's another strain to Halberstam's polemic that pits professors against students on generational terms. Here is one generation who fought hard for queer rights; who never had a Gay/Straight Alliance in high school or a way to grow up both queer and normal. Who made careers out of queer studies while they watched their administrations professionalize and their faculties casualize, who teach at universities that cost $44,000 a year to attend.

A representative of this generation calls another a bunch of babies. (So they are: their infantilization has been enforced by the privatization of public goods, by debt, and by the destruction of good jobs. Reaching puberty earlier and earlier, likely due to environmental factors, they achieve financial independence later and later, if ever. All their own fault, no doubt.)

Halberstam kind of makes a big deal of this generational gap, pointing to the "friendly adults" who erroneously install "narratives of damage that they [the youth] themselves may or may not have actually experienced." It's as if young people are stealing an earlier generation's trauma, claiming it as their own when really they have it so good. In this bizarrely counterfactual linear temporality, the past is not only past but also dead, and you do not have the right to be traumatized by historical memory, only by things that have literally happened to you—even if you are eighteen and it's all—all—news to you. We (the older generation) were there, and are over it, and so you (the younger generation) should root yourselves entirely in the ameliorated present* and get over it, because it is over.

The result is an odd polemic against coddled millenials and their too-sensitive feelings, as if it were somehow ridiculous to be young and too sensitive, or for that matter, old and too sensitive. This cross-generational call to "get over it" is an example of what Sara Ahmed has called "overing": "In assuming that we are over certain kinds of critique, they create the impression that we are over what is being critiqued." It's particularly perverse to demand that young people be "over it," when they have perhaps only just left their parents' homes, and have perhaps only recently come to any political consciousness at all. There's a very good reason college students aren't "over it"; they just got there. Have you met a college student? It's all, all new.

It is its own kind of shock to learn about how you have been historically, rather than personally, hated. It is not about "trauma" but about developing a political consciousness that is also historical, a fundamentally utopian impulse to exist in solidarity with the dead. There is, to be sure, a fine line between identifying with the past and appropriating it, but I think we can allow our students some leeway in figuring out where this line is, and not getting it right every time. Certainly grown-ups need the same leeway.

And finally, it is particularly odd to issue a generational call to turn to environmental concerns instead of LGBT activism:

What does it mean when younger people who are benefitting from several generations now of queer social activism by people in their 40s and 50s (who in their childhoods had no recourse to anti-bullying campaigns or social services or multiple representations of other queer people building lives) feel abused, traumatized, abandoned, misrecognized, beaten, bashed and damaged?

[...]

Let’s not fiddle while Rome (or Paris) burns, trigger while the water rises, weep while trash piles up; let’s recognize these internal wars for the distraction they have become.

In the words of a famous owl: O RLY?

"Don't worry about safe spaces because we 'friendly adults' already fixed that for you (whether you feel it or not); do worry about climate change because we really fucked that one up."

Well, yes we did, but maybe it's therefore our job to do the heavy lifting on that one.

I think reasonable people can disagree about trigger warning policies per se. But I don't know how any adult dares be intellectually ungenerous with the young, considering the world we've collectively brought them into. My students can take a joke, and make one. They're hilarious. And they also care about one another and try not to make those jokes at one another's expense. They're not "over" anything because they're just getting started. I'm glad they are.

-----

^Although I was not aware of a preferred pronoun and had been given to understand that Jack Halberstam does not explicitly prefer pronouns of either gender (source), two commenters have suggested that masculine pronouns are preferred. Thanks to these commenters for the correction.

*I'm granting for the sake of argument that the oppression of queer (whether "really gay" or not) youth is really the non-problem that Halberstam claims it is, but in reality this claim seems to me to be premature.

Thanks to Robin James for a helpful discussion of this piece.

Your regularly scheduled Beyoncé posts will return soon.

Friday, May 23, 2014

Beyoncé's Second Skin (Part I)

|

| Stills from "Pretty Hurts." |

In an interview with Tavi Gevinson, Lorde remarked of BEYONCE: The Visual Album (2013), "I would cry if I had to make that much visual content for an album!"

Yup, that's the point. BEYONCE: The Visual Album is a massive spectacle of occluded labor, an album that was released as a surprise, for which the question "How did she do all that?" was superseded only by "and how did she keep it a secret?" This is the narrative of perfection: all this work, made to look easy.

It seems telling that these are the refrains with which female labor, especially that of the "working mom," is greeted. Here are my top results for a Google Image search on "working mom":

|

| Top Google Image search results for "working mom." |

How does she do it? She makes it look effortless, and all the more so because we know it isn't. Repeatedly, Beyoncé trains the camera on her own beauty and the making of that beauty, and the effect is not to demystify (as in the infamous Dove ad of nearly a decade ago) so much as to centralize Beyoncé's accomplishment. The always-loaded-in-advance can women have it all? undertone to the question of can Beyoncé do it all? offers much of the album's driving tension. Clearly, as the album's success attests, Beyoncé can do it all, and yet the relentlessness of the question taps into a current of pain that seems to be female success's necessary concomitant.

|

| "Yoncé": "Tell me how I'm looking, babe." |

[I guess now is the time to observe that if you want a truly educated take on this album, it is this excellent review by Emily Lordi.]

In "Pretty Hurts," the album's first track, instead of the passive model in the Dove video whose image is altered by countless unseen agents' hands, we see a young woman deploying all the more or less painful tricks of the trade—curlers, ripping out upper lip hairs, Vaseline on the teeth (what), and, inexplicably, apparently Lysoling herself in the face (this part I truly don't understand—is it hairspray? Glade??). Although she's sometimes aided by others (at one point a woman in what looks like a HazMat suit spray-tans (?) her), mostly she has learned these techniques herself and applies them to her own body.

The video continuously cuts between before, during, and after the fictive pageant: the hours of self-crafting, the show itself, during which a losing Beyoncé has to smile and clap convincingly as another woman is crowned, the bitter aftermath. The cuts show that this is not a simple sequence of before, during, and after; preparation is always ongoing, evaluation is always ongoing, self-loathing is always ongoing. This is nowhere clearer than in the "backstage," supposedly nonperforming scenes in which Beyoncé's face snaps in and out of obligatory smiles:

|

| I want to point out that these screen shots were very hard to capture, because the transitions in and out of smiling happen so quickly. |

In fact, at one point she pulls on a smile as a man is in the process of yelling at her:

Pretty "hurts," but more than that, it's work, all kinds of work, and years of it, as we learn from the video's grainy final footage of an infantine Beyoncé Knowles, her name mispronounced by the announcer, winning a contest. "I love you, Houston," says the well-trained child, who has done what was asked of her and won.

"Pretty Hurts" announces what emerges as the whole album's preoccupation: Bildung, the making of Beyoncé and BEYONCE, the labor of performance, and not just performance as a single punctual event, but rather as a process of self-making that begins in childhood and warps time. "I do it like it's my profession," she murmurs in "Rocket," in one of the album's many unnerving invocations of sex work—unnerving because, even though she is talking about sex, it's something that could be said of almost anything Beyoncé does. What could be more professional than shooting seventeen music videos in secret while also on tour? When the song tacks on, "By the way, if you need a personal trainer or a therapist, I can be a piece of sunshine, inner peace, entertainer...," it's gratuitous; we already know—got it, Beyoncé, you can do it all! But the listing of professions in the midst of this supposedly romantic sex ballad, visualized mainly through shots of Beyoncé in lingerie, also calls attention to the professionalism that runs through everything. She can be a singer and a sexual fantasy—also a personal trainer, a therapist, a certified public accountant, a skip tracer, whatever. It's just one more thing when intimacy itself is a job.

The invocation of sex work also appears in "Partition," which opens with the infamous napkin-drop:

|

| [source] |

There's a way that this video is all over the place, and another way in which it isn't. The video frames the song's lyrics as the fantasy of a neglected wife, so unseen by her husband—whose point of view the camera eye offers us—that his newspaper covers up her face at the breakfast table.

But while we are ostensibly in the neglectful husband's visual position, we are disallowed from adopting it: the newspaper is blurry, whereas the edge of Beyoncé's hair is in focus. The video proposes a contrast between Neglected Beyoncé and Sex-in-a-Limo Beyoncé as if these were mutually exclusive roles, but only to undermine that contrast. "Partition," even more than "Rocket," insists on the labor of being a Hot Wife. Mia McKenzie reads the Napkin Drop playfully:

One of my favorite scenes in all of Beyonce’s new videos is in “Partition” when she drops that napkin just so that white woman has to pick it up. I read it as an incredible moment wherein a powerful black woman flips the script on white women who are constantly trying to put her in “her place” and in one subtle movement puts them in theirs.This reading is appealing on its face, but I think it also gets at one of the many tensions through which "Partition" operates: the ostentatious dropping of the napkin performs Beyoncé's status as mistress, not servant, but only "flips the script" because the racial politics are obvious, because we know how typically the reverse dynamic holds. We can enjoy the flipped script, but not without knowing that it's flipped, not without marking the threat that the black woman will always somehow be pulled into a role of servitude. It's the same threat that emerges in Jay-Z's infamous quotation in "Drunk in Love"—"Eat the cake, Anna Mae," a citation and apparent embrace of Ike Turner's violence against Tina Turner. Wait, more violence against black women? Again? Are we supposed to be okay with this? But it's the script (literally—from What's Love Got to Do With It) that most of "Drunk in Love" is flipping. Don't get too giddy about flipped scripts, Beyoncé seems to say. They can flip back.

A brief detour on black women flipping things around.

Consider the "topsy-turvy doll," a popular nineteenth-century toy depicting a white doll who, when her skirt was flipped over her head, revealed a black doll on the other side, and vice-versa, supposedly first made by enslaved women for the white children for whom they cared.

|

| Robin Bernstein discusses these dolls in Racial Innocence, especially pp. 81-91. |

As Robin Bernstein puts it in in Racial Innocence,

A child who minimally followed the implied script by incorporating the skirt-flip into play felt the balance of the doll, the fact that the poles weighed equally in the hands as the doll rotated. The thing scripted its user to position neither black nor white permanently on top; the competent user received the thing's message that the hierarchy could—and should—flip. With this thing, enslaved African American women scripted racial flip-flops, a perfomance of black and white in endless oscillation rather than permanent ranks of dominant and oppressed. (88)

The history of literal racial flipping scripted into African American women's artistic production looks different from the vantage point of 2013's "Queen Bey." As cleverly subversive as it is for an enslaved black woman to give her five-year-old white mistress a doll that performs hierarchy-reversal before her eyes, its proposed legacy in a rich black woman's deliberate napkin-drop has more ambiguous resonances. Script-flipping can feel wearisome—oh, that's still the script? The topsy-turvy inconsistencies of the album's positions, which have launched endless "Is Beyoncé feminist?" wars, mark the instability of hierarchy even for a black woman who has ostensibly made it.*

This instability is all the more precarious for its location at the sites of intimacy and sex; as the topsy-turvy doll also demonstrates, the flipping of scripts often occurs in the flipping of skirts, through the sexual violence with which black women are historically disproportionately targeted. "[T]he African American dollmaker sent that [white] child to bed with a sign of systematic rapes committed by members of that child's race, if not that child's immediate family," Bernstein notes. "She tucked beneath the child's blankets...a sign of the child's enslaved half-sibling, either literal or symbolic." (89) The multiple ironies of the skirt-flipping topsy-turvy doll prefigure the difficulty of pinning down a political read on a spectacle of occluded labor, a black woman whose success is so bound up in the spectacularization of her nearly-nude body.

|

| Josephine Baker |

Servitude is always at issue in "Partition," which is why the song's primary addressee is not the lover (as in "Rocket") but the limo's "driver." Seconds after establishing her difference from a servant with the napkin-drop, she sings, "Driver, roll up the partition, please;/ I don't need you seeing Yoncé on her knees." The partition, with its ability to be rolled up or down, signifies the instability of this character's place in the household. Maintaining her position as "mistress" involves not being seen "on her knees" by the servants. For whom is she performing?

Rolling up the barrier between driver and speaker, in other words, again marks the class difference between them but also the threat of that difference's flimsiness. The element of performance and of professionalism recurs with each repetition of the song's refrain: "Forty-five minutes to get all dressed up,/ And we ain't even gonna make it to this club." Getting dressed up was work, we keep being reminded. Forty-five minutes of work, 0.75 hours. This is the complaint of someone mindful of the clock.

This is why the B theme, addressed to the lover, makes so much sense. Beyoncé sings "Take all of me; I just wanna be the girl you like, the kind of girl you like" across shots of her almost hilariously spectacularized body, first just writhing in some sort of beaded wig, but quickly multiplied as what Siegfried Kracauer called the "mass ornament." Multiplied in avant-gardist seriality, the spectacle of Beyoncé's body is rendered generic and, at the same time, sublime in its sheer repeatability.

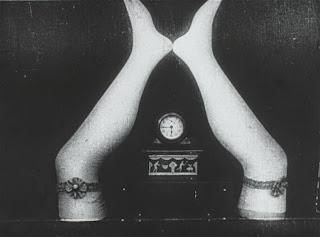

Oh, whoops, that's from Fernand Léger's Ballet mécanique (1924). Here's Beyoncé and some extra appendages:

The boundary between "the girl you like" and "the kind of girl you like" is as permeable as a limo partition (with the "chauffeur

It's not a big hop from there to Beyoncé in a cage with leopard spots, Jay-Z creepily looking on while smoking a cigar, in a move that Charing Ball quite reasonably called "groan-inducing."

Groan-inducing because it's the script, not the flip. The partition is down. And as with Josephine Baker, we can't decide if she's exploited, self-exploiting, or winning.

"I do it like it's my profession" indeed: there's a fine line between being professional and being a servant, especially if your fame and fortune rest on the commodification of your beauty and (feminine hetero-)sexuality. Sex is performance; being sexy is performance. The "Partition" video precisely cashes in on what it also critiques.

* * * * *

Part II, if/when I get around to it, will deal with Baker's and Beyoncé's glittering surfaces and the glinting conundrum that is "***Flawless."

* * * * *

*I think it's fair to say that the album does not meaningfully explore any alternative to hierarchy, which is why oscillatory scripting and script-flipping seems to mark the richest sites of its political imagination.

Thanks to @SpringaldJack for the "Partition" lyrics correction.

Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood and Race from Slavery to Civil Rights. America and the Long 19th Century. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

Cheng, Anne Anlin. Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Kracauer, Siegfried. The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Monday, May 19, 2014

I don't want to say sappy things ... um.. ever.

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:03

guess what?

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:18

i still have more to write for my diss

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:24

the acknowledgment

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:25

s

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:33

and i am terrified at the genre

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:42

having read several in other dissertations

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:47

they are horrifying

nacecire: 15:40:37

well, the first person you are going to want to thank is obviously marjorie perloff

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:40:49

they remind me of those dreadful wedding vows that people write themselves "I'll always be your pooky; I vow to save you a bite of every chocolate chip cookie I eat and to snuggle you under the blanket." Retch.

nacecire: 15:41:37

what REALLY annoys me is when people thank their therapist/yoga instructor/pet.

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:41:41

i mean, i totally have people to thank, and I want to, but I don't want to say sappy things ... um.. ever.

guess what?

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:18

i still have more to write for my diss

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:24

the acknowledgment

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:25

s

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:33

and i am terrified at the genre

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:42

having read several in other dissertations

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:39:47

they are horrifying

nacecire: 15:40:37

well, the first person you are going to want to thank is obviously marjorie perloff

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:40:49

they remind me of those dreadful wedding vows that people write themselves "I'll always be your pooky; I vow to save you a bite of every chocolate chip cookie I eat and to snuggle you under the blanket." Retch.

nacecire: 15:41:37

what REALLY annoys me is when people thank their therapist/yoga instructor/pet.

Hillary Gravendyk: 15:41:41

i mean, i totally have people to thank, and I want to, but I don't want to say sappy things ... um.. ever.

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

Elementarity and Precocity in Lorde

(Standard disclaimer: I Am Not A Musician.)

Lorde's "brand" is her precocity, and I must say that I am a sucker for it. I'm basically in total agreement with Anne Helen Peterson when she observes that Lorde's public image is both highly constructed and highly appealing.

I'm rarely able to listen to music I actually want to listen to unless I'm driving. I'm easily distracted by music and work better without it.* So, like the elderly person that I am, I listen to actual CDs straight through in my car. Driving to Philly this week I was listening to Lorde's album Pure Heroine again and thought again about something that struck me the first time I heard it: the album's relentlessly moderate tempos. Quick things happen in these songs, but always within a heavily emphasized temporal grid that, to my ear, cannot possibly be more than 120 bpm and is usually closer to 90. I looked at my watch for ten bars of "Royals" and came up with 86 bpm, although that's admittedly not the fastest song on the album. (On the other hand, it is the album's biggest single.) I am comfortable saying that moderate tempo is a Lorde tic. Not slow, but not too fast.

And I started thinking about what this might have to tell us about her precocity (acknowledging that this precocity, as we know it, is constructed). What are some other Lorde tics? Arpeggios. Parallel thirds. Simple, repetitive melodies, not just simple and repetitive in accordance the conventions of pop music, but in a way that is almost studiously elementary. If we are honest, we will notice that the refrain of "Royals" sounds approximately like what a group of six-year-olds gets up to at their Suzuki violin recital. (Even the F sharp.)

It's not just simplicity of the melody, an inverted D major triad, but also the rhythm: unsyncopated, square, neat subdivisions of time into eighth and sixteenth notes, like an exercise, announcing practice, announcing studenthood. I think Lorde's moderato is part of this elementarity, as are the self-conscious lyrical allusions to Mom and Dad, school, riding the bus, and "my first plane." As the complexity of some moments attests (I think especially of "Buzzcut Season"), Lorde does not have to be simple. But there's a formal insistence on simplicity that speaks not only to the image of authenticity that Annie points out, but also to precocity: you cannot be prococious just by being good; you have to be too young to be that good, too.

*I started playing the album when I started writing this post, then realized I needed to turn it off if I was going to write words. Argh.

Lorde's "brand" is her precocity, and I must say that I am a sucker for it. I'm basically in total agreement with Anne Helen Peterson when she observes that Lorde's public image is both highly constructed and highly appealing.

It’s clear that Lorde is precocious. She’s smart, she’s uber-literate. But she’s not just reading the classics, and she’s not checked out of popular culture. ... Many of her teen fans may not know who Laura Mulvey is, but whooo boy does a certain swath of her adult fans.GUILTY.

I'm rarely able to listen to music I actually want to listen to unless I'm driving. I'm easily distracted by music and work better without it.* So, like the elderly person that I am, I listen to actual CDs straight through in my car. Driving to Philly this week I was listening to Lorde's album Pure Heroine again and thought again about something that struck me the first time I heard it: the album's relentlessly moderate tempos. Quick things happen in these songs, but always within a heavily emphasized temporal grid that, to my ear, cannot possibly be more than 120 bpm and is usually closer to 90. I looked at my watch for ten bars of "Royals" and came up with 86 bpm, although that's admittedly not the fastest song on the album. (On the other hand, it is the album's biggest single.) I am comfortable saying that moderate tempo is a Lorde tic. Not slow, but not too fast.

And I started thinking about what this might have to tell us about her precocity (acknowledging that this precocity, as we know it, is constructed). What are some other Lorde tics? Arpeggios. Parallel thirds. Simple, repetitive melodies, not just simple and repetitive in accordance the conventions of pop music, but in a way that is almost studiously elementary. If we are honest, we will notice that the refrain of "Royals" sounds approximately like what a group of six-year-olds gets up to at their Suzuki violin recital. (Even the F sharp.)

It's not just simplicity of the melody, an inverted D major triad, but also the rhythm: unsyncopated, square, neat subdivisions of time into eighth and sixteenth notes, like an exercise, announcing practice, announcing studenthood. I think Lorde's moderato is part of this elementarity, as are the self-conscious lyrical allusions to Mom and Dad, school, riding the bus, and "my first plane." As the complexity of some moments attests (I think especially of "Buzzcut Season"), Lorde does not have to be simple. But there's a formal insistence on simplicity that speaks not only to the image of authenticity that Annie points out, but also to precocity: you cannot be prococious just by being good; you have to be too young to be that good, too.

*I started playing the album when I started writing this post, then realized I needed to turn it off if I was going to write words. Argh.

Sunday, March 2, 2014

All sorts of asses ‘love’ poetry. Why not? It confirms them in the assininity of their deepest beliefs. It underlies the racial laziness, the unwillingness to think, the satisfaction of feeling oneself part of the race and of having all posterity behind one in proneness and stupidity. This is what is inherent in most ‘love’ of poetry.

A smooth, lying meter that nostalgically carries them back to sleep is what they want. That’s why for a living, changing people only the new poetry is truly safe, truly worth reading. And that is why it is opposed by the best people—the intellectually deepest bogged—as if it were the devil himself.

—William Carlos Williams, “Note: The American Language and the New Poetry, so called” (1931?)

Labels:

modernism,

poetry,

William Carlos Williams,

zingers

Monday, January 20, 2014

By what process of logical accretion was this slight 'personality.' the mere slim shade of an intelligent but presumptuous girl, to find itself endowed with the high attributes of a Subject?—and indeed by what thinness, at the best, would such a subject not be vitiated? Millions of presumptuous girls, intelligent or not inteligent, daily affront their destiny, and what is it open to their destiny to be, at the most, that we should make an ado about it?

—Henry James, preface to The Portrait of a Lady, 1907

Wednesday, January 8, 2014

Footnotes

My essay "A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen" is out today in The New Inquiry's issue 24, "Bloodsport." Since The New Inquiry doesn't take footnotes, I am putting my footnotes here, sans context. Gotta cite those works.

Update 1/31/2014: My attention was recently brought to Daniel Goldberg's useful article "Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, the U. S. National Football League, and the Manufacture of Doubt: An Ethical, Legal, and Historical Analysis," which also uses a Geertzian framework for understanding the NFL's management of evidence.

Lindsey adds this.

1. Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru, League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions, and the Battle for Truth (New York: Crown Books, 2013), 13.

2. Clifford Geertz, “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,” Daedalus 101, no. 1 (January 1, 1972): 1–37.

3. Geertz, “Deep Play,” 27-8.

4. Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (Simon and Schuster, 1926), 136.

5. Geertz, “Deep Play,” 5.

6. Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru, League of Denial, 13–4.

7. The joke’s on us if we compare football to war. In Stephen Crane’s iconic tale of scrambling toward masculinity, “[h]e ducked his head low like a football player.” Setting aside that the comparison is already anachronistic—American football was a post-Reconstruction Era phenomenon—as Bill Brown, like Geertz, suggests, play is conventionally a structuring metaphor for war rather than the reverse. In 2011, Bennet Omalu would connect CTE, the condition he diagnosed in former Steeler Mike Webster, to post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage, and Other Stories, ed. Pascal Covici (New York: Penguin, 1991), 110; Bill Brown, The Material Unconscious: American Amusement, Stephen Crane and the Economies of Play (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1996), 2; Bennet Omalu et al., “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in an Iraqi War Veteran with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Who Committed Suicide,” Neurosurgical Focus 31, no. 5 (November 2011): E3, doi:10.3171/2011.9.FOCUS11178.

8. Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011); cf. Donna Jeanne Haraway, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse: Feminism and Technoscience (New York: Routledge, 1997).

9. Shapin and Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air-Pump, 66.

10. Claude Bernard, Introduction à l’étude de la médecine expérimentale (Baillière, 1865).

11. Ira R. Casson, Elliot J. Pellman, and David C. Viano, “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player (letter),” Neurosurgery 58, no. 5 (May 2006): E1003, doi:10.1227/01.NEY.0000217313.15590.C5.

12. See e.g. Robert Proctor and Londa L. Schiebinger, eds., Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2008). See especially Part II: Lost Knowledge, Lost Worlds.

13. In the book, Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru make a strong distinction between Omalu’s reception and McKee’s; indeed, “BU’s researchers [McKee among them] literally kept a file on what they alleged were Omalu’s exaggerations”; in the book, Omalu is widely characterized as prone to overinterpretation (epistemological immodesty). Yet the distinction is also strongly associated with Omalu’s lack of social fit—his “inappropriate” inability or unwillingness to modify his academic presentation style for a room full of football players and family members, his lack of investment in football as a cultural phenomenon, and, indeed, his foreignness. “I think [his swift sidelining from scientific discourse was] because he’s a black man, I honestly believe that,” the former linebacker Harry Carson states. “And he’s not an American black man; he’s from Africa.” McKee, in contrast, is represented as a nearly ideal figure, “with blond hair and blue eyes, a Green Bay Packers nut from Appleton, Wisconsin, with a girlish giggle and a knack for making the brain accessible and fun.” Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru, League of Denial, 290–3; 255.

14. Gregg Rosenthal, “Michael Vick: I Lied to My Mom About Dogfighting,” NFL.com, July 18, 2012, http://www.nfl.com/news/story/09000d5d82aa29a5/article/michael-vick-i-lied-to-my-mom-about-dogfighting.

15. It doesn’t end there. Vick is unpopular with “casual” fans, due to his dogfighting scandal, according to polling, but he is appreciated by “hardcore fans”—those, we might say, who “love the game.” Tom Van Riper, “The NFL’s Most-Disliked Players,” Forbes, October 21, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/tomvanriper/2013/10/21/the-nfls-most-disliked-players-2/.

16. Rosenthal, “Michael Vick”; Dan Hanzus, “Michael Vick’s Book Reveals QB’s Dogfighting Mindset,” NFL.com, July 16, 2012, http://www.nfl.com/news/story/09000d5d82a99b17/article/michael-vicks-book-reveals-qbs-dogfighting-mindset.

17. Perfetto’s occupation is mentioned in neither the documentary nor the book. Alan Schwarz, “Ralph Wenzel, Whose Dementia Led to Debate on Football Safety, Dies at 69,” The New York Times, June 22, 2012, sec. Sports / Pro Football, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/23/sports/football/ralph-wenzel-whose-dementia-led-to-debate-on-football-safety-dies-at-69.html; Alan Schwarz, “Wives United by Husbands’ Post-N.F.L. Trauma,” The New York Times, March 14, 2007, sec. Sports / Pro Football, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/14/sports/football/14wives.html.

18. As Perfetto notes, this dementia is often characterized by violent episodes, which are especially dangerous coming from exceptionally large men who are not yet old or even necessarily middle-aged. See Schwarz, “Wives United by Husbands’ Post-N.F.L. Trauma.”

Update 1/31/2014: My attention was recently brought to Daniel Goldberg's useful article "Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, the U. S. National Football League, and the Manufacture of Doubt: An Ethical, Legal, and Historical Analysis," which also uses a Geertzian framework for understanding the NFL's management of evidence.

Lindsey adds this.

1. Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru, League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions, and the Battle for Truth (New York: Crown Books, 2013), 13.

2. Clifford Geertz, “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,” Daedalus 101, no. 1 (January 1, 1972): 1–37.

3. Geertz, “Deep Play,” 27-8.

4. Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (Simon and Schuster, 1926), 136.

5. Geertz, “Deep Play,” 5.

6. Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru, League of Denial, 13–4.

7. The joke’s on us if we compare football to war. In Stephen Crane’s iconic tale of scrambling toward masculinity, “[h]e ducked his head low like a football player.” Setting aside that the comparison is already anachronistic—American football was a post-Reconstruction Era phenomenon—as Bill Brown, like Geertz, suggests, play is conventionally a structuring metaphor for war rather than the reverse. In 2011, Bennet Omalu would connect CTE, the condition he diagnosed in former Steeler Mike Webster, to post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage, and Other Stories, ed. Pascal Covici (New York: Penguin, 1991), 110; Bill Brown, The Material Unconscious: American Amusement, Stephen Crane and the Economies of Play (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1996), 2; Bennet Omalu et al., “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in an Iraqi War Veteran with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Who Committed Suicide,” Neurosurgical Focus 31, no. 5 (November 2011): E3, doi:10.3171/2011.9.FOCUS11178.

8. Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011); cf. Donna Jeanne Haraway, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse: Feminism and Technoscience (New York: Routledge, 1997).

9. Shapin and Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air-Pump, 66.

10. Claude Bernard, Introduction à l’étude de la médecine expérimentale (Baillière, 1865).

11. Ira R. Casson, Elliot J. Pellman, and David C. Viano, “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player (letter),” Neurosurgery 58, no. 5 (May 2006): E1003, doi:10.1227/01.NEY.0000217313.15590.C5.

12. See e.g. Robert Proctor and Londa L. Schiebinger, eds., Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2008). See especially Part II: Lost Knowledge, Lost Worlds.

13. In the book, Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru make a strong distinction between Omalu’s reception and McKee’s; indeed, “BU’s researchers [McKee among them] literally kept a file on what they alleged were Omalu’s exaggerations”; in the book, Omalu is widely characterized as prone to overinterpretation (epistemological immodesty). Yet the distinction is also strongly associated with Omalu’s lack of social fit—his “inappropriate” inability or unwillingness to modify his academic presentation style for a room full of football players and family members, his lack of investment in football as a cultural phenomenon, and, indeed, his foreignness. “I think [his swift sidelining from scientific discourse was] because he’s a black man, I honestly believe that,” the former linebacker Harry Carson states. “And he’s not an American black man; he’s from Africa.” McKee, in contrast, is represented as a nearly ideal figure, “with blond hair and blue eyes, a Green Bay Packers nut from Appleton, Wisconsin, with a girlish giggle and a knack for making the brain accessible and fun.” Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru, League of Denial, 290–3; 255.

14. Gregg Rosenthal, “Michael Vick: I Lied to My Mom About Dogfighting,” NFL.com, July 18, 2012, http://www.nfl.com/news/story/09000d5d82aa29a5/article/michael-vick-i-lied-to-my-mom-about-dogfighting.

15. It doesn’t end there. Vick is unpopular with “casual” fans, due to his dogfighting scandal, according to polling, but he is appreciated by “hardcore fans”—those, we might say, who “love the game.” Tom Van Riper, “The NFL’s Most-Disliked Players,” Forbes, October 21, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/tomvanriper/2013/10/21/the-nfls-most-disliked-players-2/.

16. Rosenthal, “Michael Vick”; Dan Hanzus, “Michael Vick’s Book Reveals QB’s Dogfighting Mindset,” NFL.com, July 16, 2012, http://www.nfl.com/news/story/09000d5d82a99b17/article/michael-vicks-book-reveals-qbs-dogfighting-mindset.

17. Perfetto’s occupation is mentioned in neither the documentary nor the book. Alan Schwarz, “Ralph Wenzel, Whose Dementia Led to Debate on Football Safety, Dies at 69,” The New York Times, June 22, 2012, sec. Sports / Pro Football, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/23/sports/football/ralph-wenzel-whose-dementia-led-to-debate-on-football-safety-dies-at-69.html; Alan Schwarz, “Wives United by Husbands’ Post-N.F.L. Trauma,” The New York Times, March 14, 2007, sec. Sports / Pro Football, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/14/sports/football/14wives.html.

18. As Perfetto notes, this dementia is often characterized by violent episodes, which are especially dangerous coming from exceptionally large men who are not yet old or even necessarily middle-aged. See Schwarz, “Wives United by Husbands’ Post-N.F.L. Trauma.”

Saturday, January 4, 2014

Humanities scholarship is incredibly relevant, and that makes people sad.

Man, two of them today, one in 3am Magazine (h/t Robin James) and one in the relentlessly regressive WSJ (remember this guy, whose cranky pan of the Cambridge History of the American Novel is a classic of this genre?), h/t Noel Jackson.

Don't bother clicking; you've already read it a hundred times. It's the article titled "The Humanities Are Relevant and I Hate That."

The humanities are often represented as an irrelevant, moribund, and merely preservationist field, passing on old knowledge of old things without producing anything new. That's why it keeps having to be "defended" by people saying, "no! old shit matters too!" (It does—witness one chapter from Washington Irving's 1819-20 Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. getting rebooted yet again, this time as a goofy paranormal procedural—but this already accepts a basic misrepresentation of humanities scholarship.)

Yet it’s precisely the production of new knowledge in the humanities that powerfully influences the everyday lives of Americans, and which leads to pearl-clutching by those who insist on the humanities’ irrelevance. David Brooks, for example, is very sad that the humanities have failed to be stagnant. He claims that humanities enrollments have substantially declined (factually untrue) since the rise of critical theory and its concurrent attention to race, class, gender, sexuality, and disability in the 1980s. But the humanities didn’t just turn to these categories for kicks (still less because it was “fashionable,” as culture-wars critics like Alan Sokal have claimed); turning to them was the result of research. Through research, scholars found out that these categories were complicated, powerful, and important for understanding culture. Brooks seems to suppose that doing research that has a broad impact makes your field irrelevant. This is deranged.*

Do you know a black child who grew up knowing about America’s great traditions in African American literature, visual art, music, and film? Are you glad Their Eyes Were Watching God and Cane are in print? Then thank the scholars, artists, and activists who have recovered that work—often obscured by a racist publishing culture and by an academy that didn’t think it was important at the time. There’s a reason that students protested and sat in to fight for the establishment of ethnic studies and women’s studies departments in the 1960s and 70s. It wasn’t a fashion statement: serious formal engagement with the cultural contributions of women and ethnic minorities was urgently needed. No one can credibly say in public that women cannot be great authors anymore, for example, and when the writer V.S. Naipaul tried in 2011 (and David Gilmour in 2013), everybody knew how ridiculously wrong he was. How did they know? Thank the humanities. Thank those horrible feminist critics from the '80s who allegedly ruined literary scholarship. They worked like hell to change the language, and most of them never got famous.

Why does my cousin complain about her high heels as a way of bonding with other women?** Why does the criminal justice system so routinely view black minors not only as criminal but also as non-children? Why do gender and sexual categories like “male,” “female,” “gay,” “straight,” or “trans” have such an outsized effect on the way that you and I experience public space? The humanities address the questions, big and small, that we urgently want answered. Answers often lie in the history of the way that we’ve mediated these problems, in cultural artifacts like novels, poems, newspapers, visual art, music, and film. Sorting through, analyzing, and theorizing those artifacts is the business of the humanities.

Academic humanities scholars do this very well, but non-university-affiliated people engage in humanistic work all the time. (Let's NOT give all the credit for the above to academics—many of whom are still firmly in the crankypan/ts camp and hold great influence. A great deal of this work was led by activists and non-academics—but that's my point: the academic humanities are not hermetically sealed off from the rest of the world in the way that some believe, or that David Brooks and Heather Mac Donald would like.) If you're a "completist" who has to watch every Eric Rohmer film you can, you’re doing humanities. When you decide you need to watch every single episode of every single Star Trek franchise, and when you decide to write about it on a blog or in a forum, you’re still doing humanities. You’re doing humanities if you write Harry Potter fanfiction to reinterpret the world of Hogwarts as a place where gay romances can flourish, or where characters of color aren’t relegated to supporting roles. (Humanities scholars study fanfiction, too. Cue the pearl-clutching about the decline of Standards.) Sometimes books by academics are difficult to read, because they’re specialized and technical and reference a lot of things you haven’t read. That’s fine; it’s harder to read an academic science journal than it is to read National Geographic, too. We may not always notice the ways that academic concepts are circulated and reinterpreted in popular culture, but that's because we live and breathe it every day. Just like scientific research, humanities research constantly crosses in and out of the academy, and it’s so much a part of everyday life that most of the time we don’t even bother to think of it as “humanities.”

The interpretation of culture and of cultural artifacts is everywhere, whether we’re deciding whether a book or television show is appropriate for a child, parsing an ambiguous email from someone we love, or trying to understand out a falling out among friends. The academic humanities are the serious, formal study of such interpretation. And that interpretation fundamentally—not incidentally—involves the conceptual categories that shape everyday life, including race, class, gender, sexuality, and disability. Interpretation is social. It's political.

My hunch is that some people would rather that the humanities weren’t as relevant as they are, and have projected a distorted image of a self-involved, isolated profession in order to justify defunding the very research that makes the humanities so important. “Pay no attention to the research that’s going on here! It’s irrelevant!,” they insist. They wish that instead of doing new research on under-studied archives, bringing public attention to hidden histories, or offering new and challenging ways to think about the categories that most shape politics and everyday life, that we’d pipe down and eternally reproduce old, unchanging narratives about the usual suspects. They wish not only that we’d keep teaching about Thomas Jefferson (which we do, happily), but also that we’d keep teaching him the same way, forever, never bringing to light new historical evidence (Sally Hemings, anyone?***) or reinterpreting his writing through theoretical frameworks that bring new insight [Duke journals paywall]. They wish it were mere faddishness causing the humanities to do this kind of work. Sorry, guys: it’s evidence.

They stereotype us as standing up in front of a classroom and teaching the same old syllabus in the form of lectures that remain the same from year to year. But they only wish that were true. In reality, humanities scholars continually rethink their syllabi, taking into account recent research in the field, new approaches in our own research, and successes and failures in our previous teaching, which rarely takes the form of lectures. That’s because at the university level, the humanities, like every other field, is a field in the making. New knowledge is being created all the time, and that’s a good thing.

It seems to me that when pundits deride the humanities as irrelevant, it’s because we aren’t, and that poses a threat. Yes, studies in the humanities do raise uncomfortable questions, like when Susan Reverby, a women’s studies professor at Wellesley, documented a series of horrific unethical medical experiments that the U.S. Government performed on Guatemalan prisoners in the 1940s. They do make you change your textbooks. They challenge firmly held beliefs about culture, and offer evidence to back it up. People who want humanities research to be "timeless" do not believe that it can or should be timely. They are wrong.

-----

Many thanks to Tressie McMillan Cottom for comments on an earlier version of this post.

*Yes, I violated my #neverclick rule. For you, dear readers.

**Not a real cousin.

***Historical research on Sally Hemings actually comes up in the aforementioned goofy paranormal procedural yes I admit I have watched it. It was all the tweets about the show using Middle English that drew me in. (By the way: Middle English in the 1590s? Wtf?) The point is: time-traveling eighteenth-century Ichabod (yeah, very loose adaptation) doesn't know about Sally Hemings but EVERYBODY in the present day does. THANK YOU, ANNETTE GORDON-REED.

I wish I could have a "BEYONCE as Bildung" symposium with all my students from last semester. I know they would rock it.

Don't bother clicking; you've already read it a hundred times. It's the article titled "The Humanities Are Relevant and I Hate That."

The humanities are often represented as an irrelevant, moribund, and merely preservationist field, passing on old knowledge of old things without producing anything new. That's why it keeps having to be "defended" by people saying, "no! old shit matters too!" (It does—witness one chapter from Washington Irving's 1819-20 Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. getting rebooted yet again, this time as a goofy paranormal procedural—but this already accepts a basic misrepresentation of humanities scholarship.)

Yet it’s precisely the production of new knowledge in the humanities that powerfully influences the everyday lives of Americans, and which leads to pearl-clutching by those who insist on the humanities’ irrelevance. David Brooks, for example, is very sad that the humanities have failed to be stagnant. He claims that humanities enrollments have substantially declined (factually untrue) since the rise of critical theory and its concurrent attention to race, class, gender, sexuality, and disability in the 1980s. But the humanities didn’t just turn to these categories for kicks (still less because it was “fashionable,” as culture-wars critics like Alan Sokal have claimed); turning to them was the result of research. Through research, scholars found out that these categories were complicated, powerful, and important for understanding culture. Brooks seems to suppose that doing research that has a broad impact makes your field irrelevant. This is deranged.*

Do you know a black child who grew up knowing about America’s great traditions in African American literature, visual art, music, and film? Are you glad Their Eyes Were Watching God and Cane are in print? Then thank the scholars, artists, and activists who have recovered that work—often obscured by a racist publishing culture and by an academy that didn’t think it was important at the time. There’s a reason that students protested and sat in to fight for the establishment of ethnic studies and women’s studies departments in the 1960s and 70s. It wasn’t a fashion statement: serious formal engagement with the cultural contributions of women and ethnic minorities was urgently needed. No one can credibly say in public that women cannot be great authors anymore, for example, and when the writer V.S. Naipaul tried in 2011 (and David Gilmour in 2013), everybody knew how ridiculously wrong he was. How did they know? Thank the humanities. Thank those horrible feminist critics from the '80s who allegedly ruined literary scholarship. They worked like hell to change the language, and most of them never got famous.

Why does my cousin complain about her high heels as a way of bonding with other women?** Why does the criminal justice system so routinely view black minors not only as criminal but also as non-children? Why do gender and sexual categories like “male,” “female,” “gay,” “straight,” or “trans” have such an outsized effect on the way that you and I experience public space? The humanities address the questions, big and small, that we urgently want answered. Answers often lie in the history of the way that we’ve mediated these problems, in cultural artifacts like novels, poems, newspapers, visual art, music, and film. Sorting through, analyzing, and theorizing those artifacts is the business of the humanities.

Academic humanities scholars do this very well, but non-university-affiliated people engage in humanistic work all the time. (Let's NOT give all the credit for the above to academics—many of whom are still firmly in the crankypan/ts camp and hold great influence. A great deal of this work was led by activists and non-academics—but that's my point: the academic humanities are not hermetically sealed off from the rest of the world in the way that some believe, or that David Brooks and Heather Mac Donald would like.) If you're a "completist" who has to watch every Eric Rohmer film you can, you’re doing humanities. When you decide you need to watch every single episode of every single Star Trek franchise, and when you decide to write about it on a blog or in a forum, you’re still doing humanities. You’re doing humanities if you write Harry Potter fanfiction to reinterpret the world of Hogwarts as a place where gay romances can flourish, or where characters of color aren’t relegated to supporting roles. (Humanities scholars study fanfiction, too. Cue the pearl-clutching about the decline of Standards.) Sometimes books by academics are difficult to read, because they’re specialized and technical and reference a lot of things you haven’t read. That’s fine; it’s harder to read an academic science journal than it is to read National Geographic, too. We may not always notice the ways that academic concepts are circulated and reinterpreted in popular culture, but that's because we live and breathe it every day. Just like scientific research, humanities research constantly crosses in and out of the academy, and it’s so much a part of everyday life that most of the time we don’t even bother to think of it as “humanities.”

The interpretation of culture and of cultural artifacts is everywhere, whether we’re deciding whether a book or television show is appropriate for a child, parsing an ambiguous email from someone we love, or trying to understand out a falling out among friends. The academic humanities are the serious, formal study of such interpretation. And that interpretation fundamentally—not incidentally—involves the conceptual categories that shape everyday life, including race, class, gender, sexuality, and disability. Interpretation is social. It's political.

My hunch is that some people would rather that the humanities weren’t as relevant as they are, and have projected a distorted image of a self-involved, isolated profession in order to justify defunding the very research that makes the humanities so important. “Pay no attention to the research that’s going on here! It’s irrelevant!,” they insist. They wish that instead of doing new research on under-studied archives, bringing public attention to hidden histories, or offering new and challenging ways to think about the categories that most shape politics and everyday life, that we’d pipe down and eternally reproduce old, unchanging narratives about the usual suspects. They wish not only that we’d keep teaching about Thomas Jefferson (which we do, happily), but also that we’d keep teaching him the same way, forever, never bringing to light new historical evidence (Sally Hemings, anyone?***) or reinterpreting his writing through theoretical frameworks that bring new insight [Duke journals paywall]. They wish it were mere faddishness causing the humanities to do this kind of work. Sorry, guys: it’s evidence.

They stereotype us as standing up in front of a classroom and teaching the same old syllabus in the form of lectures that remain the same from year to year. But they only wish that were true. In reality, humanities scholars continually rethink their syllabi, taking into account recent research in the field, new approaches in our own research, and successes and failures in our previous teaching, which rarely takes the form of lectures. That’s because at the university level, the humanities, like every other field, is a field in the making. New knowledge is being created all the time, and that’s a good thing.

It seems to me that when pundits deride the humanities as irrelevant, it’s because we aren’t, and that poses a threat. Yes, studies in the humanities do raise uncomfortable questions, like when Susan Reverby, a women’s studies professor at Wellesley, documented a series of horrific unethical medical experiments that the U.S. Government performed on Guatemalan prisoners in the 1940s. They do make you change your textbooks. They challenge firmly held beliefs about culture, and offer evidence to back it up. People who want humanities research to be "timeless" do not believe that it can or should be timely. They are wrong.

-----

Many thanks to Tressie McMillan Cottom for comments on an earlier version of this post.

*Yes, I violated my #neverclick rule. For you, dear readers.

**Not a real cousin.

***Historical research on Sally Hemings actually comes up in the aforementioned goofy paranormal procedural yes I admit I have watched it. It was all the tweets about the show using Middle English that drew me in. (By the way: Middle English in the 1590s? Wtf?) The point is: time-traveling eighteenth-century Ichabod (yeah, very loose adaptation) doesn't know about Sally Hemings but EVERYBODY in the present day does. THANK YOU, ANNETTE GORDON-REED.

I wish I could have a "BEYONCE as Bildung" symposium with all my students from last semester. I know they would rock it.

Wednesday, January 1, 2014

Why is it that at the “same time” capital grows more virtual and abstract in its daily operations, cultural critique grows increasingly positivistic and empirical, veering away from the methods best suited for the analysis of its proliferation? (300)

—Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)